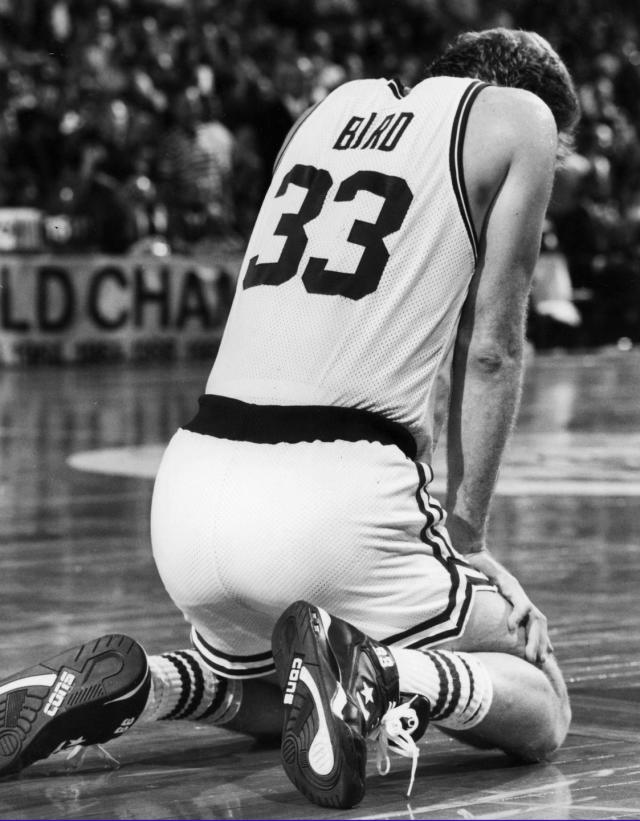

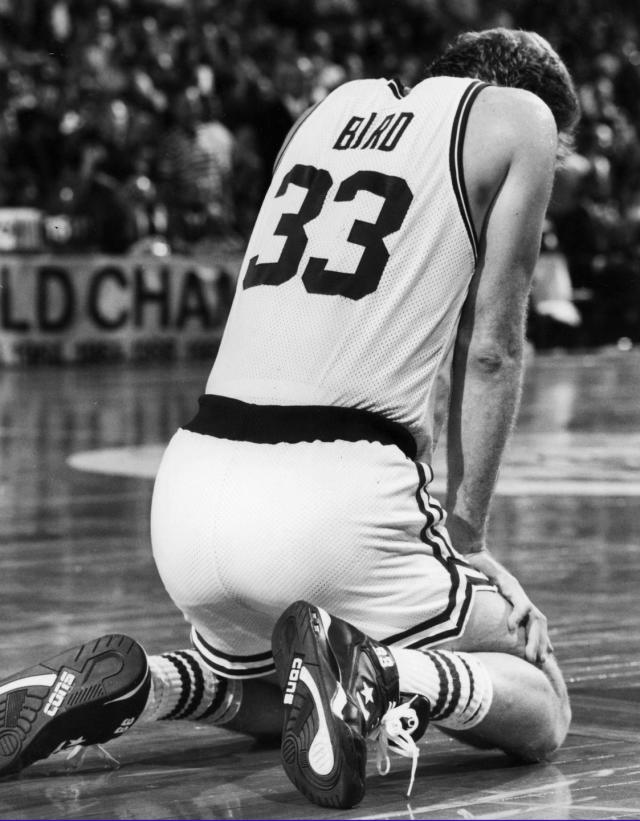

SAD NEWS: I WILL NEVER PLAY AGAIN FOR Larry Bird

You first see Larry Bird’s jumper up close in December 1984 at the Omni pregame shootaround. Bigger, blonder than on TV, he drains shot after shot, swish after swish. You strain on tiptoes, age eight, and your father scoops you up and sets you on his shoulders and wraps his hands around your ankles. Not all swishes are equal. Some swush as if Bird has spotted a bull’s-eye within a bull’s-eye.

You live in Atlanta as Hawks fans, but your dad grew up south of Bird in New Albany, Indiana. He’d trained at various points to be a pastor, lawyer, and professor, but instead of a congregation, court, or classroom, he has you for an audience. Together, you share Larry Bird. Each morning, he recounts Bird’s box scores, and the digits spin through your school days. He tags tales of Bird with the refrain that Larry Bird was once a garbage man, lacing our official record with this article of faith. A god? Swish swish swush. A garbage man. With each shot Bird takes at the Omni, your dad squeezes your flesh hard enough to leave a mark.

You’ll never get closer to Bird, the north star of your youth, but he’s present in every debate and stretch of silence with your dad. This is true even on that December night in 1991 when your world stops, spins off its axis, and leaves you on a sidewalk seeing stars. He could not catch you then, for there are places the child must go where the father cannot follow. Your dad pointed beyond Bird to the unfinished project of America. It wasn’t a lesson you wanted. It required vision. To see the whole floor. To recall the game’s one time greatest player, who hitched home after twenty-four days at Indiana University to work as a garbage man. You didn’t want a lesson. You wanted to beat your old man in one-on-one and he would not, under any circumstance or weather, yield.

Inside the cold, fluorescent-lit room at the Internal Revenue Service, rows of massive computers generate numbers that refuse to add up for your father. As a computer programmer for the IRS during the summer of 1991, in the last days of Larry Bird, your dad brings his work and the numbers home. Your own number is fifty. Fifty free throws. You both shoot fifty in sets of ten. Your dad keeps count.

Bird shoots one hundred. Sets of twenty. His goal? One hundred straight. When he gets ninety-nine in a row, he banks the last one. “There were some days,” Bird tells The Indy Star in 2015, “I couldn’t miss. I could try to miss and wouldn’t.”

At the line, your dad sinks free throw after free throw and recounts Bird at the line against the Clippers, immune to the tricks of the San Diego Chicken. He details the left-handed jumper of New Albany’s Terry Morrison, who played AAU with Bird for Hancock Construction. He then asks if you know what’s happening to Hoosier families right now. Poor families like the Birds once were. Farm families in Fort Wayne? Working families in Gary? You don’t. You’re fourteen. “Right now,” he says, “and across America, the rich hoard third homes and second yachts while steelworkers and mill workers donate blood to feed their families.”

His words form a background noise, a music you try to tune out. When he tells you to bend your knees deeper and hold your follow-through longer, you tune in. Swish.